I tend to shy away from discussions of a religious nature, because there is usually not much objective information exchanged. The only way, I say to myself, that I would touch the topic, is if there was actually some evidence that was not purely subjective or opinion-oriented in nature. However, I thought of an empirical question that interested me: does being religious and actively engaging in religious activity actually make people any better off in terms of their wellbeing than people who don’t do this?

I think this is an interesting and more relevant question than the done-to-death ‘is there a God?’. If actively participating in customs and behaviours, prayer etc has no effect at an individual level, then the existence of such a being is entirely irrelevant. Of course, there are many theories and ideas that discuss benefits and drawbacks to religion and religious behaviour. However, in what follows, I’m going to approach this on a purely empirical basis, and let you decide what conclusions to draw.

Religion and Wellbeing

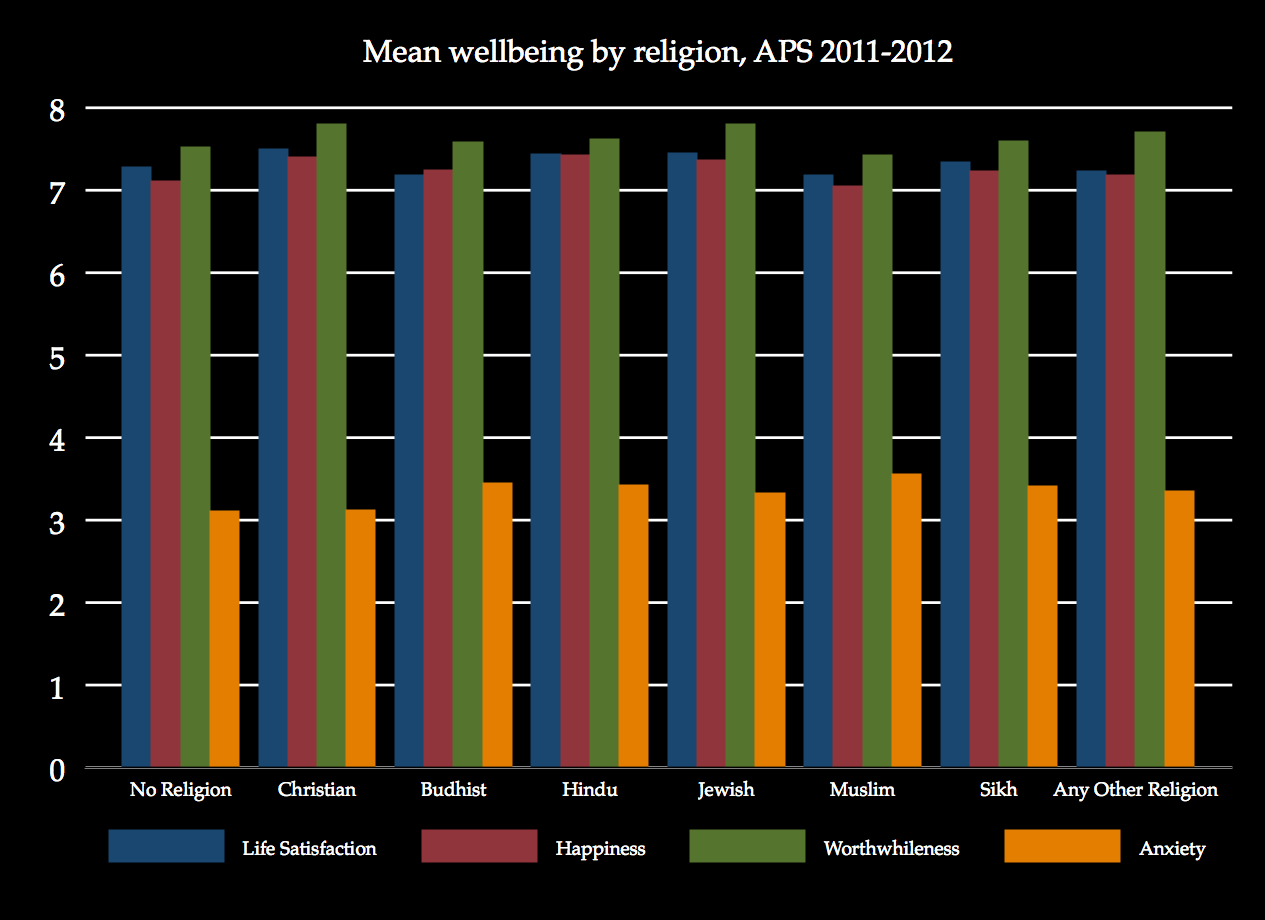

Let’s just look at some raw correlations for the UK. I’m using data from the Annual Population Survey 2011-2012. There are 4 standard subjective wellbeing questions that are asked to respondents, and they have to score themselves on a scale that goes from 0 to 10.

If we perform some very simple regressions to test how being a part of each major religious group in the UK correlates with wellbeing, it seems quite clear that Christians are much better off in terms of overall life satisfaction than any other religious group. Compared to non-religious people, Christians in the UK on average have 0.2 points more life satisfaction. Hindus fare the best in happiness, being 0.3 points happier than the non-religious. Christians and Jews are just under 0.3 points higher in rating the worthwhileness of their lives compared to the non-religious.

In fact, the only religious group that consistently fall short of the non-religious in the UK are Muslims. In particular, they are almost half a point more anxious in general than the non-religious (though people from all religious groups are slightly more anxious than the non-religious). They are also less satisfied with their lives and feel their lives are less worthwhile.

Of course, this doesn’t say anything about being a Muslim in general, but it does tell us that being a Muslim in the UK is associated with worse wellbeing. One may well find the opposite relationship in a predominantly Muslim country. All of the above findings are significant with p<0.01, and with over 160,000 observations.

Adding Controls

Of course, there are a lot of other things that affect our happiness and wellbeing. Failing to control for them in regressions leads to something called omitted variable bias. This basically tells us that if we miss an important determinant of wellbeing, then the actual ‘effect’ of religion on wellbeing will be biased. In other words, that 0.2 higher satisfaction for Christians that we saw earlier could be as a result of Christians also being more wealthy in the UK. If that were true, then when we control for income, the effect of being Christian on wellbeing is likely to shrink (or disappear entirely).

I repeat what I did earlier, but now I take into account the following additional factors:

- General health level

- Age (and age-squared)

- Gender

- Country within the UK

- Marital status

- Wage (which implicitly tells us about employment status too)

- Whether the person has a degree or not

We do lose some observations by including these, but the sample is still large at 63,780. Unsurprisingly, including these things changes a lot of the results we get. The strongest positive relationships with life satisfaction are health level and whether you are married (or in a civil partnership). However, it is still true that Christians are more satisfied with their lives than non-religious people, just less so. Now, being Christian only increases your satisfaction level by 0.09 points. All other religious groups are no different in satisfaction terms to non-religious people… apart from Muslims. Including these factors actually paints a worse picture for Muslims. Life satisfaction for them is 0.2 points lower than the non-religious, which is double the effect that I found just in the basic regression earlier.

For happiness, the evidence generally points to little religious effect. Only Christians receive strong happiness benefits, along with people from other unclassified religious groups. Jews have a very strong happiness benefit, but the result is less statistically significant (p=0.07). Muslims are still more anxious than non-religious people, but now this effect is matched in both Sikhs and Hindus. Finally, only Christians find their lives more worthwhile than non-religious people. All other religious groups are no different to the non-religious in terms of worthwhileness.

Health Levels

“Hang on!” you say. “What if being religious is actually having an effect on our wellbeing by increasing our general health?” Well, we can test that too. Running the same regression, but sticking health as the dependent variable, we don’t find anything too different to what have already seen.

Christians are the only religious group to be healthier than the non-religious, but the effect is not very large. All other religious groups, apart from the Jewish, are significantly less healthy than non-religious people. Of course, this doesn’t mean being religious causes ill health. It could, for example, mean that people who have poor health are drawn to religion to help them out psychologically.

Power of Prayer

Up until now, we have found patterns that are only due to religious group affiliation. A lot of people report themselves to be Christian (or another religion), but do not actively engage or participate in any religious behaviour. Also, the strength of belief is not assessed, so it may be that someone reports themselves as Christian because they were brought up in that environment, even if they are practically closer to being agnostic.

Therefore, a more interesting question, is whether active religious participation, like praying, makes any substantive difference. Unfortunately, as you might expect, data about these kinds of thing is a bit more difficult to come by.

There is a question in the 2008 British Household Panel Survey that asks people whether they actively participate in religion. There are not many observations, just 1,629. But when we run a regression, it seems that those who are actively religious do have higher life satisfaction than those who don’t. The difference is around 0.17 points on a 1-7 scale, however, so it isn’t a huge effect. There is some evidence that these people are healthier as well, but the result is not very statistically significant, and is only 0.08 of a point in magnitude. In comparison, employed people are almost 0.5 of a point healthier, and people who have a degree are 0.2 of a point healthier.

Summary

There’s a lot of information here, and there’s a lot of effects flying around at the same time. I will leave it up to you to make sense of the results. What it seems is that the negative relationship between various religious groups and wellbeing is likely to be social in nature rather than spiritual. Moral rules of conduct and public perceptions about your religion are possibly going to affect your wellbeing more than whether you pray or not.

I do find that there is some evidence in support of actively participating in religion, in wellbeing terms. This may involve things like prayer and adhering to various codes of conduct. But, there isn’t enough evidence here to say religious activity is a causal factor.

Probably the most important thing to note from all of this is that things like employment, education, and your relationship status are generally far more important contributors to your wellbeing and life satisfaction than religious affiliation or practice. If religious activity can help to improve these other factors, then it may well be beneficial. However, if this is actually taking time away from more tangible activities that are directly related to goal pursuit (like learning a new skill), then it could prove to be counter-productive for wellbeing improvement in the long run.