Bands like Genesis, Muse, Metallica, and Dave Matthews Band have something important in common. They started out with music that was somewhat ‘against the grain’, attracting a specialist audience of listeners. Once they became more established, however, their music shifted towards more mass-market appeal, attracting the wider majority. I’m sure you can think of examples of bands which you liked, but felt subsequently ‘sold out’ in their later years. Conversely, you may also be able to think of bands that you liked in their later years, only to discover that they had an earlier library of music that you listened to but found inaccessible.

I mentioned the phrase ‘sold out’ already. It seems that common wisdom has already come up with an explanation for this behaviour – a simple case of profit-seeking that sees bands try to appeal to people with the most dollar. This is probably true in essence. Rather than being an active snub to fans, however, game theory can offer an explanation that suggests it may just be an inevitable move for survival.

Hotelling’s Idea

The explanation for this phenomenon comes as early as 1929, by the economist Harold Hotelling. His idea was the following: imagine there is a street that is long and straight. There are 2 shops on the street, both selling one identical product for the same price. So if you are a shopper, you are going to buy from the shop that has the cheaper cost, i.e. the one with the lowest travel cost required to get there.

The question is: where should the 2 shops locate themselves to get as much of the market as possible? Assuming that customers are uniformly distributed along the street, the best thing to do is for the two shops to be on opposite ends of the street. This way, each shop gets exactly half of the market. They have their own niche of consumers on the street.

Crucially, this model can be used as an analogue for product differentiation. It doesn’t have to be a physical street in practice. Firms might locate on opposite ends of the spectrum in terms of their brands (e.g. a shoe firm that markets their products to young people, and another that markets to older people).

How can we apply this to music? Well, consider the case of two bands who have a very strong niche. One might start out writing heavy thrash metal songs that the average person finds too abrasive. The other might produce progressive rock songs that are too complex and long for the average person. However, if these were the only two bands around, then people would have to choose one or the other. Let’s call them Red and Blue, for argument’s sake.

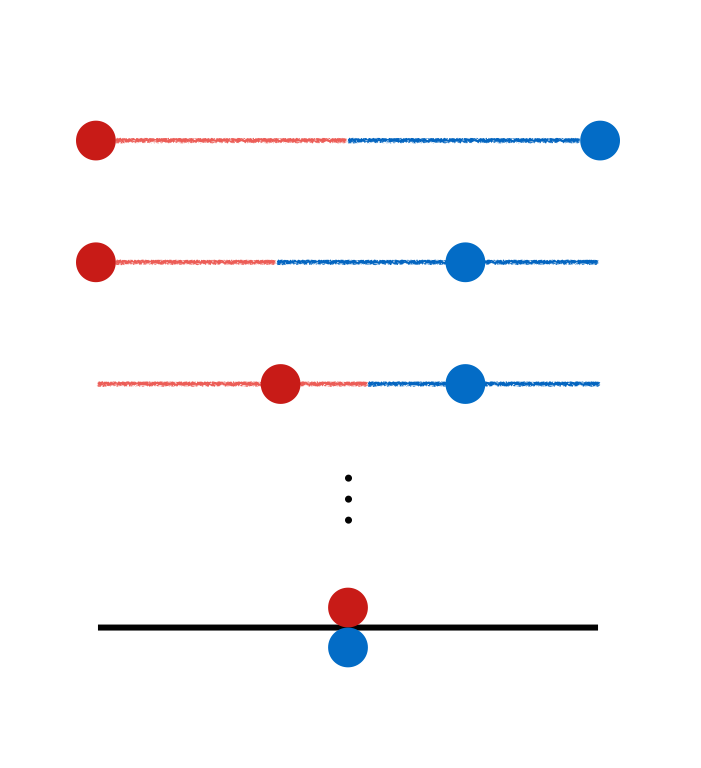

They are starting out on opposite ends of the ‘street’, or product spectrum. Because of this, they each capture about half of the listeners to begin with. Remember, each listener is represented by a point on the line, and their position represents their taste. The fans left of the middle have more of a Red preference, and the fans on the right have more of a Blue preference.

Now suppose we introduce the possibility of movement over time. This is what will happen:

Blue realises that by releasing an album with some slightly shorter and simpler songs, it can capture more listeners. The fan who is split between the two bands is now someone who is located more to the left than the previous indifferent fan. That old indifferent fan now clearly favours Blue. In other words, by becoming a bit more mainstream, Blue has captured more of the overall number of listeners. Red realises that the only people coming to their shows are people wearing hockey masks. They decide to transition from trash metal to the more accepted realms of hard rock. Now the indifferent fan is located right of centre, and Red has more of the overall listeners.

Eventually, if this process is allowed to continue, both bands will position themselves dead in the middle. They end up producing music that is accessible to the highest number of people. Each band has now given up the ‘niche’ position they had at the start and now just write generic rock. As a result of this, they each lose all of their ‘devoted fans’ who are loyal to their brand of music, and still attract fans, but have no way of distinguishing themselves from one another.

This is not an ideal situation for either band, but it is an equilibrium. What this means is that if one band decides to move away from the centre independently, they are going to be worse off than before, because they will lose fans to the other band. Thus, we have a situation where bands end up becoming generic, and are somewhat stuck there.

In practice, when a band has made enough money, often they will go back to explore more extremes, because now the value they gain from a specialist fan has increased above the value gained from a generic fan. Alternatively, it might take new bands to shake things up again and redefine niches.

In any case, the Hotelling idea is quite a powerful one. It explains why products can tend towards the generic over time if there are no other restrictions or features of the market that might prevent this. Remember this as you sit in puzzlement, wondering how these guys:

became these guys: